- Home

- Richardson, Lance

House of Nutter Page 3

House of Nutter Read online

Page 3

Four months later, a letter from the Ministry of Works arrived at the café advising “T. A. Nutter, Esq.” that he was now a clerical assistant. “Your starting pay will be £4 17s. 0d. per week, rising to £5 10s. 6d. per week on your birthday in April, 1960,” the letter informed him. “Up to the age of 18 you will be entitled to a meal voucher valued ⅛d. and purchasable for 10d. You will also be allowed time off (a day each week) to attend school, if you wish, until you are 18.”

What this actually meant was that Tommy had essentially become an office chai wallah. Fetching tea left him “practically insane with boredom,” and he spent most of his time staring at the scratched surface of his wooden desk. During Tommy’s tenure, the Ministry of Works was finalizing designs for the Post Office Tower (now the BT Tower), a centerpiece of the country’s modern telecommunications network that would dramatically alter the London skyline with its bulbous figure. If Tommy took any notice of what was happening around him, though, he never gave any indication. Instead, his attention seemed focused elsewhere—on himself, on what he was wearing. “I shall never forget my first suit,” he later recalled, and he would recall it so often and with such wistfulness that the suit came to seem almost talismanic, a glorified relic for which he’d paid £8. Bought from Burtons, it featured a short, square jacket in brown worsted, narrow lapels, three covered buttons, and tapered trousers with slits up the ankles: what was called “the Italian Look.”

Tommy loathed the Ministry of Works. Administrative bureaucracy was, he decided, tedious and “dismal.” He endured it for nine months, got his pay raise. And then, on November 8, 1960, he bought a copy of the Evening Standard, turned to Situations Vacant, and alighted on an advertisement.

SAVILE ROW TAILORS have vacancy for youth to learn trimming, packing and general shop duties. Little knowledge of tailoring preferred, but not essential. Good appearance and manner important. Apply in writing. G. Ward & Co., 35 Savile-row. W. 1.

Tommy would later claim that he’d always had a natural flair for dressing well. At the technical college he’d woken up to the idea of personal style, had kept his little white shirt carefully well ironed (“or at least my mother did”), and his hair parted, creamed, and combed into a peak. The advertisement now spoke to him, and it seemed to say, “Come on, if you don’t do it now you’ll never do it.”

The following day, Tommy wrote an application letter using his most painstaking penmanship.

…Unfortunately I have no experience of the tailoring trade, but I am sure I will pick it up very quickly, because I am very interested in it.

Should you be so good as to offer me the vacancy I would use every effort to fill the post to your satisfaction.

Yours faithfully,

Thomas A. Nutter.

Tommy mailed the letter without telling his parents. When they found out, “their feeling was one of amazement,” Tommy recalled. “They had always wanted me to find a steady, secure job. Tailoring did not fit into that category.” Christopher, for his part, was “not exactly pleased about the idea.”

But Tommy didn’t much care about his father’s opinion, and he was through with blindly following convention for the sake of security. He’d tried things their way, Dolly and Christopher’s; now it was his turn. “I knew from a little boy what I wanted to do,” he once told a journalist, glamourizing the facts only a little. “And I went against everything to do it.”

Chelsea Bridge and the Battersea Power Station

A regular workday, 1960: Tommy is dodging men in black bowlers, traffic conductors, scooters, and women whose skirts seem to be getting shorter these days; past tobacconists and newsagents, florists, hair salons, cosmetics shops, immigrant-run restaurants selling foods that he’s never heard of, let alone eaten; past dank, unpaved alleyways, seedy cellar spaces, and low-slung windows coated in grime; and past narrow espresso bars with those newfangled Gaggia machines, where the kids are “packed tight,” just as Colin MacInnes wrote, “whispering, like bees inside the hive waiting for a glorious queen bee to appear.” This labyrinth—Soho—unfurls all the way to Charing Cross Road, a gauntlet populated by boys much like Tommy rushing cans of celluloid from one production house to the next, by drunkards and prostitutes, by people cruising down around Piccadilly for anonymous sex.

As an “errand boy-trotter,” or deliveryman, Tommy has a bag on his back filled with toiles and valuable cloth. He comes to a door and pushes inside, then climbs a staircase to a cramped workroom, where men sit cross-legged, squinting, beneath lighting that will probably destroy their eyesight before the end. These men, called outworkers, look up from their boards at the new arrival, who promptly distributes his cargo: cloth to be assembled into coats go to the coat makers (a popular saying: “Gentlemen wear coats, potatoes wear jackets”); and trouser pieces go to the trouser makers. Everyone has his specific role, an area of expertise. Some have callused ridges on their fingers from years of repetitive exertion.

Tommy collects any garments the outworkers have completed and folds them gingerly into his bag. Then, mission accomplished, he dashes down the stairs and retraces his path back through the squalidness to Regent Street.

A canyon carved from gray-white Portland stone, Regent Street divides this part of London into two distinct realms: louche Soho in the east; genteel Mayfair in the west. A river of black cabs and red buses rushes in between. Tommy bridges the canyon at the traffic lights, adjusts his pace, and begins a respectable stroll toward the famous stretch of Savile Row.

* * *

Say, today, that you have some serious money in your pocket, £3,000 to £6,000, and an overwhelming desire to buy a suit so finely made it will immediately diminish everything else in your wardrobe to the level of rags. On Savile Row, do you go to the tailors your father has gone to (and grandfather before him, for his military uniforms), Dege & Skinner? Or is your primary interest a signature house style: the slim-looking single-button coats at Huntsman, perhaps, as skillfully balanced as a samurai sword? If old Hollywood is an influence, you might follow Rudolph Valentino into Anderson & Sheppard, just around the corner on Old Burlington Street. Of course, Henry Poole & Co. is always a safe bet too, having been favored by everyone from tsars and shahs to Charles de Gaulle, who led the Free French during the Second World War while looking immaculate.

Whichever firm you choose to patronize, the process of bespoke is largely the same. During a first consultation, a salesman, attentive but not obsequious, will begin by peppering you lightly with questions. What suits do you already own? And what is the intended event for this one: a wedding, a law office, a film premiere? What’s the weather like where you plan to wear it, because that will influence the cloth selection (worsted wool, linen, mohair, tweed, flannel…). And then, of course, there is the matter of design: pinstripes, windowpane, Glenurquhart check? Single- or double-breasted? If you happen to be the indecisive type, this step alone might take several hours, which is exactly why alcohol is often on standby.

Eventually a cutter will be summoned to the front, a star employee, confident and persuasive, who is supremely educated in all aspects of the craft. The cutter usually has at least seven to eight years of experience; in the past, tailors have been known to claim, with proud exaggeration, that training a cutter “takes longer than to train a brain surgeon.”

The cutter’s first charge is sizing you up. Accompanied by one or more assistants, sometimes called strikers, he (or she, if the firm is particularly progressive) will wrap and poke a tape measure in up to two dozen different ways, charting the topography of your body with unnerving precision. He will also observe your figuration—the way you hold yourself, the way you move. Physical measurements are recorded as a list of numbers; figuration, however, might become a series of covert abbreviations, meaningless to all but those in the know.

DR: Sloping down on the right shoulder

RB: Rounded back

&

nbsp; FS: Flat seat; no backside

The cutter will ask his own questions. With tact and subtlety, for example, he may inquire whether you “dress left” or “dress right”—which way your manhood tends to fall in your underpants.* Unsurprisingly, this intimate collaboration between client and cutter has assumed a special status in tailoring lore, a status that a Playboy fashion director once summed up like this: “They used to say that the relationship of a man to his tailor was like a woman and her gynecologist—all private.”

The cutter combines technical skill with subjective interpretation; mathematics with art. This becomes particularly true once you’ve played your part and vacated the premises. Standing at a workbench before a wide expanse of clean manila paper, the cutter looks over your details and, using a piece of chalk, sets about translating them into an original pattern. He may do this using a drafting square and French curves, jotting down equations based on long-held principles of scale, proportion, and balance.

“A corpulent man may, and, if of true type, does, hold himself erect to counterbalance the weight of his abdomen.”

Or he may just wing it. If complex geometry is second nature, his preferred cutting system will be “rock of eye,” or the rule of thumb, meaning he’ll sketch out your coat freehand, using almost nothing but a refined instinct for graceful lines. All details of the suit—angle of the gorge, sweep of the lapel—will then be inflected by those idiosyncrasies of hand that make some cutters good and others astounding.

Once finished, your pattern will be safeguarded in the firm’s storeroom for decades. In the future, whenever you visit for a new suit, alteration lines will be added to reflect the passage of time, until the pattern becomes, in effect, a palimpsest of your life. Many years ago, Poole employed a man who acted as an in-house librarian, his primary job to maintain thousands of numbered patterns on shelving in a vast basement. His secondary job was to read The Times obituaries every morning: if a client’s name happened to appear, he would locate their pattern and “get rid of it,” effectively closing the record.

Eventually your pattern is transferred to approximately three and a half yards of cloth. Extra lines are added for pockets and vents. Then the cutter (perhaps running shears through his hair to ever-so-lightly oil the blades) strikes out each of the requisite panels, or has an able assistant do it for him. There is no room for sloppiness here. “Cutting bespoke suits is almost the hardest thing in the world if you’re really into it,” explains Rupert Lycett Green, who ran a tailoring firm near Savile Row from 1962 until the early 1980s. “You’re trying to create things of beauty. If you’re Michelangelo, you can take a bit of stone and keep at it until it’s perfect. But if you do that with a suit—well, then the man goes on holiday and comes back eight pounds heavier, or takes up marathon running and comes back eight pounds lighter. You’ve got to alter it. There’s tremendous pressure.”

The first fitting is a subdued affair. You return to the showroom and pull on a ragged-looking “skeleton baste,” tacked together with white cotton thread. The cutter dances around, slashing you with more chalk marks to refine your silhouette. This is generally done away from a mirror: people who gaze at themselves tend to stiffen their posture in an unconscious act of self-magnification.

Following the fitting, the baste suit is unstitched, ripped flat, recut if necessary, and then built, on average, for eighty hours. Give or take a dozen.

If you’re of the rare breed able to appraise your own body honestly, then by the second or third fitting you will begin to understand what makes these suits so exceptional. The materials and feel, of course, as well as the way it makes you feel, like you’re wearing a carapace. But there is also something more: what could be called the sartorial airbrushing.

A master tailor “must be able not only to cut for the handsome and well-shaped, but bestow a good shape where nature has not granted it; he must make the clothes sit easy in spite of a stiff gait or awkward air…” So decreed the Dictionary of English Trades in 1804, and the principle remains true more than two hundred years later. Take, for instance, a man with a slight frame, sloping shoulders, and an abnormally large head: a Savile Row suit can pad up his shoulders by multiple inches, and be draped to emphasize his chest and hips, thereby making his head seem more flatteringly proportioned. Just look at Archibald Leach: this is precisely what the consummate experts at Kilgour, French & Stanbury did to help turn him into Cary Grant.

On Savile Row, this magic trick is executed with a particular attitude that only enhances the effect. Hardy Amies, the couturier and fashion designer, once wrote, “A man should look as if he had bought his clothes with intelligence, put them on with care and then forgotten all about them.” The Italians call this idea sprezzatura: studied carelessness, artifice concealed behind an appearance of casual ease. A good suit is not really supposed to draw attention when you wear it; it should, in fact, be all but invisible as it corrects for your deficiencies, the implication being that no corrections are even taking place. Archie Leach was not transformed through the tireless effort of a team of craftsmen; he was simply Cary Grant, already perfect, who just happened to be wearing a suit he picked up somewhere in London.

The magic of a Savile Row suit, which rarely looks new in the conventional sense, is that it enhances your real self into heightened fantasy, then presents this fantasy as your real self.

* * *

“I started off picking up pins,” Tommy once recalled of his first job at G. Ward & Co. He landed the position after skipping a day of work at the Civil Service, which docked his pay in penalty. “I think they were rather desperate to have somebody sweep the floor,” he said, though in truth he was experienced for G. Ward in exactly the right ways: processing mail, running parcels around town, delivering tea to more senior employees. The pay was just as abysmal as in the Civil Service—£5 10s. per week—and yet it hardly seemed to smart this time around: “I was so keen I loved every minute of it.”

G. Ward occupied a modest showroom at No. 35 Savile Row, with space behind it and below for cutters and storage. All traditional tailors at the time refrained from window displays or outward flourishes of any kind. The sole concession, perhaps, would have been a small brass nameplate that recalled the sign on a law office or funeral parlor. Window glass was heavily frosted, admitting light from the street, but not curiosity: either you knew what was there or you would never know, were not meant to know. The hoi polloi was carefully segregated from an esteemed clientele that included the English conductor Sir Adrian Boult; Hugh Gaitskell, leader of the Labour Party; and the Grand Ducal Family of Luxembourg.

Later in life, Tommy would describe G. Ward as “rather an old-fashioned company,” even “a bit stuffy.” But he was an attentive observer who absorbed everything he could about the tailoring trade: the variations of button (horn, corozo nut), the proper number for a coat, how many should be fastened when the coat was being worn. Rules of dress fascinated Tommy in the same way that some people are fascinated by feng shui. He learned, for example, how to measure quality by scrunching cloth and reading the creases. He trained his eye to spot one suit sleeve two millimeters longer than the other. He practiced the tailor’s lingo until he was fluent, acquiring the full arsenal of obscure (and devastating) abbreviations.

SLABC: Stands like a broken-down cab horse

Tommy’s attentiveness soon got him promoted out of the broom closet and into the cutting room, where he assumed a new role as trimmer, meaning he was responsible for organizing interlinings, buttons, and thread—all those trimmings (thus the name) that go into making up a single garment beyond the cloth.

In the cutting room, Tommy was exposed to the customs and traditions of Savile Row tailoring, many of which could be traced back to George “Beau” Brummell, a Regency-era dandy who’d effectively become (and remains today) the patron saint of bespoke tailors, for reasons enumerated by Virginia Woolf: “His clothes seeme

d to melt into each other with the perfection of their cut and the quiet harmony of their colour. Without a single point of emphasis everything was distinguished—from his bow to the way he opened his snuff-box, with his left hand invariably.” Tommy would come to trust in the gospel of Brummell so completely that he would one day preach it authoritatively on BBC Radio.

By 1961, Tommy had enrolled in night classes at the Tailor & Cutter Academy on Gerrard Street, in Soho. Under the tutelage of A. A. Whife, he completed the six-month cutter’s course; later, he would credit it with teaching him “how to actually make a jacket and properly fit a sleeve,” which may have been something of an overstatement. According to Andrew Ramroop, a tailor who once considered attending the school himself, Tommy “learned pattern drafting, he learned the rudiments of translating measurements onto paper.” If a cutter can be likened to a brain surgeon, the academy taught Tommy just enough to be a nurse.

While Tommy went about his studies, the West End continued to change all around him. The city of London had never seen so many cars on its roads. Postwar prosperity meant Ford Anglias, Morris Minors, and, most recently, the fabulous, head-turning Mini. Parallel parking was a particularly vexing issue in areas like Mayfair, the lanes of which had never been envisaged to accommodate automobiles.

In March 1962, The Times published a notice that sent a grumble of discontent through the workrooms of Savile Row.

FROM OUR ESTATES CORRESPONDENT

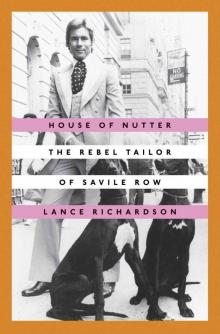

House of Nutter

House of Nutter